Stephen Campbell

Aug 31, 2019

8/10

Bill O'Reilly: You can take some of your lyrics, such as, "You'll understand when I'm dead." I mean, disturbed kids could take the lyrics and say, "you know, when I'm dead, everybody's going to know me."

Marilyn Manson: Well, I think that's a very valid point, and I think that that's a reflection of, not necessarily this program, but of television in general - if you die and enough people are watching, then you become a martyr, you become a hero, you become well-known. So when you have things like Columbine and you have these kids that are angry and they have something to say and no one's listening, the media sends a message that if you do something loud enough and it gets our attention, then you will be famous for it. Those kids ended up on the cover of Time magazine twice. The media gave them exactly what they wanted.

- Marilyn Manson speaking with Bill O'Reilly; The O'Reilly Factor (August 20, 2001)

The movie's inspired by Apple News updates, and the way that you have four or five top stories; basically, at any given time, there's usually some coverage of a mass murder and maybe something about Ariana Grande having cut off her ponytail. In 20 or 30 years, when we're at the mid-century mark and we have a little perspective, what are the events that we will identify as having defined this time? I do think that there's been a major shift in the culture since Columbine and 9/11, and now we've had an even greater tectonic shift with this new administration. When people look back, they remember Britney Spears along with 9/11. Popular music is just a way of talking about the popular culture.

- Brady Corbet; "Vox Lux's Brady Corbet on Making One of the Most Polarising Movies of the Year" (Charles Bramesco); Vulture (December 7, 2018)

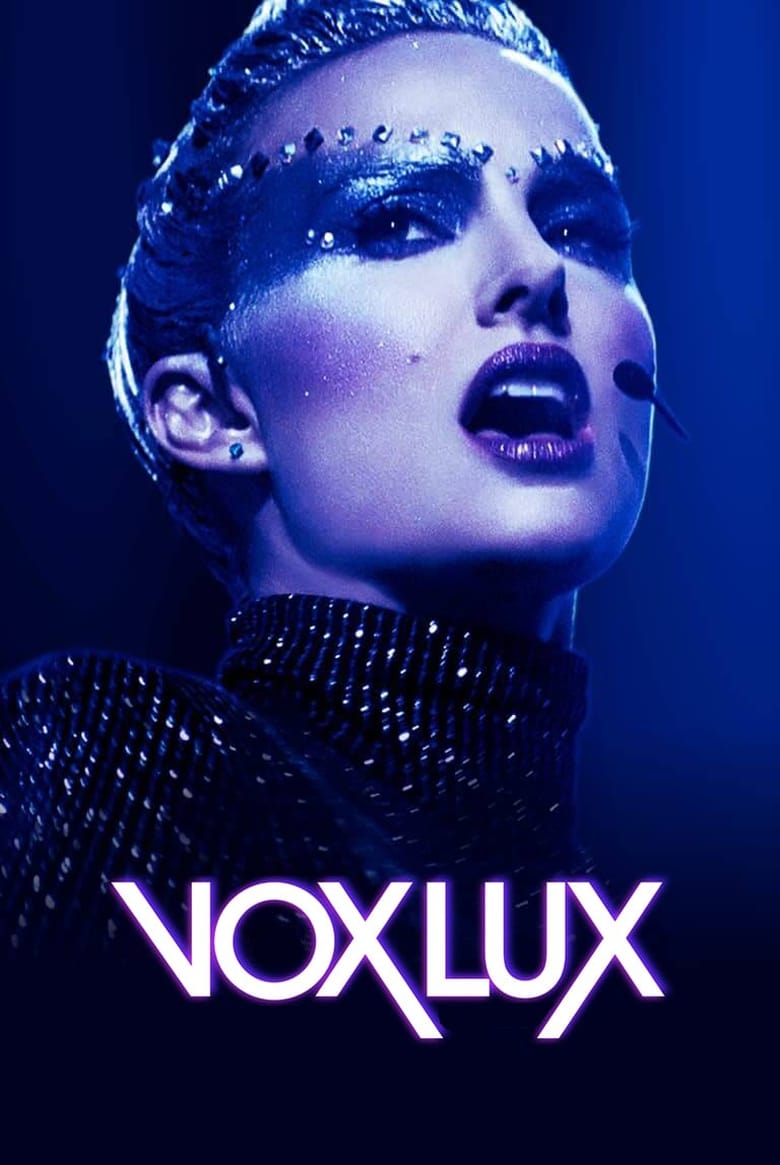

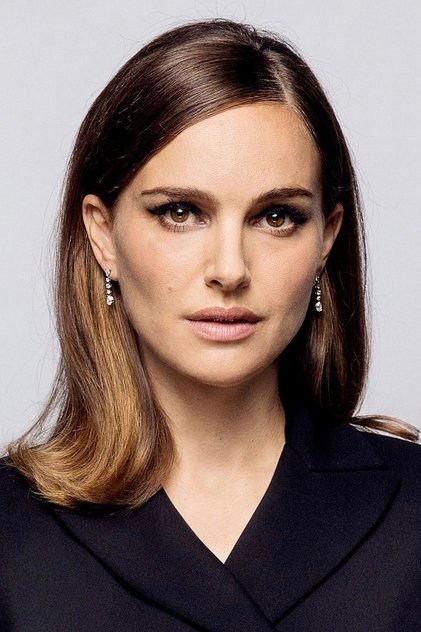

Celeste was born in America in 1986. Considering her parents' background, education, and socioeconomic status, being somewhat on the losing side of Reaganomics, the name of Latin origin seemed an especially poetic choice. It carved her out some predetermined destination, a route by which to travel. But many years before "Celeste" rolled off the cultural tongue like a principled anecdote one senses they were born knowing, she might not have been described as all that special or conspicuously talented. However, she did possess that proverbial "something," which on occasion captured the attention of her teachers and young peers.The narration does have an important thematic purpose, however, serving as a kind of omniscient chorus on events, with Dafoe describing it as "an important tonal element and framing device. It's a kind of go-between with the audience". Also aesthetically important is the music. The unashamedly over-produced and plastic songs sung by Celeste are all written by Sia (although they're performed by Cassidy and Portman), whilst the score is provided by the legendary Scott Walker, whose music so elevated the grandeur of Childhood of a Leader. He's more restrained and contemplative here, but it's still an exceptionally important component of the film, and represents the last piece of original work before his untimely death earlier this year. In terms of the acting, there's no weak link. Tapping into some of the same energy she possessed in Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan (2010) and some of the same nuance she showed in Pablo Larraín's Jackie (2016), Portman plays adult Celeste as suitably frazzled. Holding nothing back, her histrionic but always authentic depiction of a woman on the edge of a total breakdown is mesmerising to watch, whilst a concert sequence is as bravura a piece of acting as anything from Black Swan. In the dual role of young Celeste and Albertine, Cassidy does enough to differentiate the parts, but not so much as for the roles to seemingly have no connection to one another; her Celeste is all overwhelmed and innocent, struggling to maintain control, whilst her Albertine is stoic and world-weary, mature before her years. Jude Law's unnamed manager is just sleazy enough to be disreputable but just honest enough to be likeable, whilst Jennifer Ehle's Josie is wonderfully haute, permanently looking down on pretty much everyone around her, Law in particular. Thematically, the film's most salient concern is a cynical deconstruction of celebrity and fame, specifically the 21st-century post-reality TV incarnation of such (there's a reason the closing credits give the film the subtitle, "A Twenty-First Century Portrait"). In an era whereby one can become famous for virtually anything, the film is painfully of its time, saying as much about celebrities and the machinery of fame as it does about celebrity-obsessed culture. Important in this is that there's no real attempt to make adult Celeste likeable or sympathetic. Sure, she's very much a product of her time, and she's been forced to live her entire life within the parameters of what happened when she was 13. But she's also emblematic of some of the worst components of her time, and Corbet is unconcerned whether the audience empathises with her; his critique of celebrity works just as well if we despise her and all she represents. Of course, much of the film's biting satire is tied into the plot itself, with Celeste building a career based off a massacre; gun violence used to sell records (a nice visual representation of this is that Celeste turns the neck scarf she has to wear post-shooting into a glittery accessorised part of her brand). She is literally the beneficiary of tragedy in a world where mass shootings have become so commonplace that they can serve as launch-pads for musical careers. Indeed, Corbet is one of very few American directors operating at the moment who is too young to have really known a world in which such incidents weren't an accepted part of the cultural fabric (he was 11 when Columbine happened), and this feeds into the film's DNA. Although the shooting with which the film opens is fictional, it is obviously based on Columbine (both occur in 1999), whilst the shooting in Croatia seems derived from the 2015 massacre at Port El Kantaoui. And obviously, 9/11 looms large, forming the closing punctuation to Act I, with Corbet able to use the transition to subtly suggest that post-9/11 everything has fundamentally changed. Celeste herself articulates an important element of the connection between pop culture and mass murder when she says, "nihilist radical groups perceived as superstars. If everyone stopped talking about them, they'd disappear", which is very reminiscent of the main theme in Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers (1994), and which is an even more pertinent sentiment today than it was in 1994. By way of illustration, think about how most people know the names of the Columbine shooters, or the 2012 Aurora shooter, or the 2017 Las Vegas shooter, or, to get away from the US, the 2011 Utøya shooter. Now think about how many victims from any of those tragedies you can name off the top of your head. People know the names of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold; very few know the names of William "Dave" Sanders, Jon Curtis, or Jay Gallentine, the Columbine teacher and two janitors who saved over 100 students, at the cost of Sanders's life. Vox Lux doesn't provide any answers to the question of the crossover between pop culture and terrorism - how one might lead to the other, or how both provide opportunities for fame - but that's because there are no easy answers. It's simply the way things are, and Corbet's cynicism emphasises that just because this is the way things are, doesn't mean this is the way they should be. And the irony at the heart of the film is that in 1999, a mass shooting shaped Celeste, but in 2017, Celeste shaped a mass shooting. This is the nightmare of the 21st-century celebrity wheel of time, and it's brilliantly, if distressingly, presented. There are more grounded engagements with celebrity as well. An early scene, for example, sees Celeste proudly declare that she's "in command of her own destiny", followed immediately by a scene of her vomiting into a toilet after drinking too much. In another scene, Corbet brilliantly nails the drudgery of press junkets that every celebrity seems to despise, with Celeste trying to talk about her album, but all any of the journalists want to talk about is the shooting in Croatia. Another aspect of this, and something the film has in common with Cooper's A Star is Born, is that as time goes on, Celeste moves further and further away from her stylistic origin point. Introduced as a good Christian girl into folk music and gentle ballads, when we meet her as an adult, she's an autotuned, silicon amalgamation of Madonna, Katy Perry, and Lady Gaga, with her music just one step above boy band quality (as she herself says, "I don't want people to have to think too hard. I just want them to feel good"). However, she's also wildly popular, and her music clearly does make people feel good, even if it says precisely nothing of interest or note (which is, of course, ironic considering that her breakthrough came with a song that spoke volumes to the entire world, giving voice to unspoken collective grief). In terms of problems, there are a few. Obviously, any film with such lofty aims as mapping the ideological decline of 21st culture onto the rise and fall and rise of a pop star is setting itself a huge task, and at times Corbet's ambitions exceed his reach. Parts of the adult Celeste portion of the film definitely stray into melodrama, and the fact that the first act is so good does make the second seem a little prosaic in comparison (although the Finale is mesmerising). The ambiguity of the first act, which is unclear if Celeste's rise to fame is redemptive or an extension of the evil unleashed in the shooting, gives way in the second to the far more mundane (and clichéd) study of a harried celebrity, and although the totality is satisfying, I couldn't shake the feeling that the first act seemed to be setting up for something upon which the second fails to deliver. The tone of the film is also ice-cold, and in tandem with its sardonic attitude, could rub some people the wrong way. Nevertheless, this is a vicious, deeply cynical, deeply sardonic, and deeply ironic dissection of contemporary culture and the forces that drive it. However, finding much to criticise in the millennial pop landscape, Corbet is never nihilistic, mainly because Celeste may have lost her soul, but she is still able to make millions of people happy, even if only transitorily. Both a victim of her time and its desensitised apotheosis, through her, much as he did through Prescott in Childhood of a Leader, Corbet explores questions relating to the interaction between the private and the public. Where are we as a society? What does our obsession with celebrity say about us? What is the cost of fame? Is there any real difference between fame and notoriety? Vox Lux asks such questions, but does not provide answers. That's not Corbet's remit; he merely holds up the looking glass. What we see in it is entirely up to each of us.