Great style, precious little substance

In most movies like this, these sort of psycho, sexual thrillers, the female character is there to be a damsel in distress, there to be naked or there to be killed in a really brutal way. This movie sets up, here's a guy who wants to kill a prostitute, so you think the movie is getting to deliver all those things, but it so doesn't. The beauty of Mia's character is that she doesn't let herself be any of those tropes, she doesn't let herself be a damsel in distress, get killed, be taken advantage of; she really is the one with all the power and the one that's playing on the mind games.

- Nicholas Pesce; "Nicolas Pesce on His Film Adaptation of Murakami Ryu's Piercing" (Eric Ortez Garcia); Screen Anarchy (October 2, 2018)

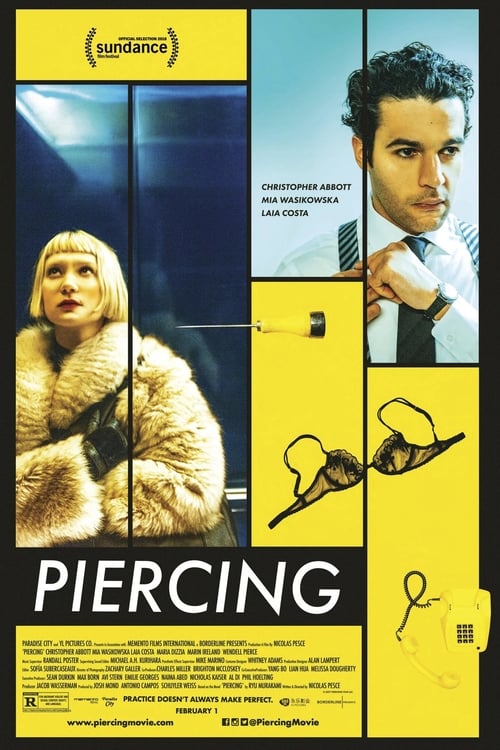

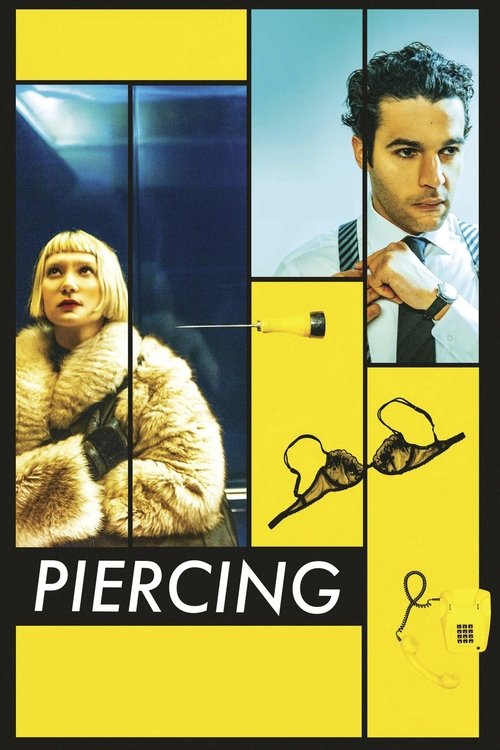

From Nicholas Pesce, the writer and director of

The Eyes of My Mother (2016), and based on the 1994 novel by Ryû Murakami (who also wrote the novel upon which Takashi Miike's similarly themed

Ôdishon (1999) was based),

Piercing is a darkly comic psychosexual thriller. Partly a screwball comedy about a fastidious man's attempt to murder a prostitute, and his confusion and helplessness when he realises that that prostitute is far more disturbed than he is, the film dares the audience to attempt to figure out who is in charge at any given moment, and to ponder whether one (or both) of these characters would actually be quite happy to be the other's victim. Purposely made to look like a sleazy seventies skin flick (the kind you might expect to see being shot on

The Deuce), the film's sense of nostalgia drips off the screen, manifest in everything from the music borrowed from giallo films to the art-deco production design to the patently fake urban skyline to the lurid opening credits (complete with retro "Feature Presentation" card). In this sense, Pesce is a stylist, in the best sense of the term. However, at the moment, he is a stylist without much to say; as in

The Eyes of My Mother, he is unable to match his not-inconsiderable aesthetic acumen with any kind of significant or tangible emotionality. The two leads are not necessarily the type of characters we're naturally predisposed to feel empathetic towards, but we surely must be expected to feel

something. Anything. However, with no real sense of psychological verisimilitude nor much in the way of interiority, they remain essentially blank canvases, and primarily for this reason, the film feels more like a sketch than a finished product.

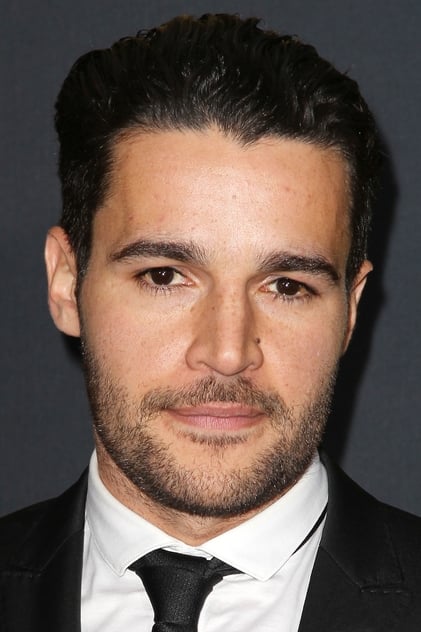

Set in a non-specific city, the barely-there plot concerns Reed (Christopher Abbott), the clean-cut kind of psychopath about whom the neighbours would undoubtedly say, "he was always such a nice quiet young man." Reed has been having some less-than-wholesome thoughts about his new-born baby, and as the film begins, he's standing over the baby's cot, ice-pick in hand, trying to resist the urge to kill the infant. Only when his partner, Mona (Laia Costa), awakens and calls out to him, does Reed regain his faculties. He then explains, in voice-over, his plan to entrap a prostitute in a hotel room, and murder and dismember her, thus purging himself of the desire to kill his own child. Telling Mona he is going on a business trip, Reed checks into a hotel and books a prostitute who is open to S&M (this way he'll be able to tie her up without her becoming suspicious). Planning every aspect of the murder, he rehearses everything from how long the chloroform will leave her unconscious to how best to carry her to the bathroom to begin the dismemberment, and records every detail in a small book. However, when the prostitute arrives, things go down-hill fast, as Jackie (a superb turn from Mia Wasikowska) is far from completely sane herself. Immediately beginning to masturbate, she throws Reed off his game-plan, causing him to laugh nervously. Seemingly annoyed, she retreats to the bathroom, and refuses to come out. After knocking repeatedly on the door to no avail, Reed, who is still hopeful of being able to salvage the evening's homicide, opens the door and walks in on her. Then things get very weird.

Partly a film about coming to terms with desires deemed fetishistic by society, and partly an erotic thriller about two people who seem genuinely confused as to whether they're teammates or opponents, the film's most salient theme is, perhaps, the issue of sexual consent, and how easily muddled it can become. It's a brave theme to take on in this post #MeToo era, with the film daring to ask whether consent should still be applicable if a person has consented to something harmful to their person, even up to the point of consensual homicide. Although there's no cannibalism in the film, the storyline reminded me a little of the 2001 case of Armin Meiwes. Looking for a volunteer to eat, Meiwes posted an online ad, "

for a well-built 18- to 30-year-old to be slaughtered and then consumed." The ad was answered by Bernd Jürgen Brandes, who went to Meiwes's home, where the two made a four-hour video which depicted Meiwes killing Brandes with Brandes's complete consent, and eating parts of him. Initially sentenced to eight years in prison for manslaughter, Meiwes was re-tried in 2005, after a German court argued he had killed for sexual gratification. Meiwes claimed he had only killed Brandes because Brandes asked him to do so, and sexuality had nothing to do with it, but in 2006, he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. The film doesn't deal with the case explicitly, but the shifting sexual power-play between Reed and Jackie, and the fact that at least twice, one of them believes they've been granted permission to murder the other, raises similar moral issues.

Within the parameters of this theme, one of the most obvious aspects of the film is its sense of humour, with many of the laughs coming from how utterly anal Reed is. Half Patrick Bateman, half Frank Spencer, once an unpredictable human element is introduced into his scheme, he finds himself unable to think on-the-fly. As his meticulously laid plans go up in smoke, he proves comically inept at handling any kind of interpersonal relationship (one wonders how he ever wooed Mona). However, the fact that most of the comedy lands on his shoulders throws into relief perhaps the film's most egregious problem; although a good 90% of the narrative is told from his perspective, there's precious little to his personality. Granted, a couple of final-act flashbacks fill us in on why he is so obsessed with murder, but his character simply isn't capable of filling out the film's 81 minutes. And there's less character detail on Jackie than there is on Reed. And there's even less character detail on Mona than there is on Jackie. Despite this, Wasikowska gives a superb performance, all facial tics, unspoken volatility, and nervous mannerisms, with an almost balletic way of moving. The actress is able to find far more psychological nuance in the character than is ever hinted at in the script.

I'm not familiar with Murakami's novel, but I gather that much of the character background that is noticeable by its absence from the film is very much present in the book. According to a colleague of mine, the novel's main focus is the psychology of the two leads (in the novel, Reed's character is Kawashima Masayuki, and Jackie's is Sanada Chiaki), exploring the ways in which childhood trauma lingers into adulthood, manifesting itself in unexpected and exceptionally destructive ways. This aspect has been all but stripped away from the film (apart from the brief aforementioned flashbacks). I'm also told the dark comedy aspect is relatively unique to the film, with the novel working more like a tragedy. In this sense, Pesce seems to have made a conscious choice to trim the book's character beats back to their barest elements, replacing the psychological verisimilitude with a self-depreciative sense of humour and ultimately pointless kinky power-play. Indeed, speaking to Indiewire, Pesce states,

>

the script probably started out darker than the movie became, but I think through the process of making the movie, we saw what kind of wackiness there was potential for. Particularly in a lot of Japanese literature, there is this awesome sense of humour about the darkest stuff. And while it works differently in a book than it does in a movie, I think through the course of making it, we found how playful it was.

The problem for me is that nothing in the film really lingers – and when some of the imagery is this extreme, it should definitely linger. For example, I've never been able to completely forget my first viewing of

Ôdishon – not because of the violence per se, but because the film spends so long building up the character of Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi), so that when those needles and that wire saw come out, you absolutely feel the weight of what is about to happen. In

Piercing, I don't really think there's any depravity that Reed and Jackie could have inflicted on one another than would have provoked an emotional response, because I didn't know them, and therefore was unable to care about them, as people.

Aesthetically, however, there's a great deal to praise here, with the sound design particularly inventive. During Reed's rehearsal of the murder, he goes through the entire act, from the initial drugging to the dismemberment. On screen, we see him pantomime the actions, but on the soundtrack, we hear the disturbing foley of everything – so as he's miming sawing, we hear a saw cut through flesh and bone. It's a brilliant way to place us firmly within his subjective experience, and it also serves to remind us that the innocent looking Reed is very much planning to do real harm to someone. On a similar note, the music is absolutely top notch. Eschewing an original score, the film instead employs pre-existing tracks primarily from giallo films, including Goblin's scores for Dario Argento's

Profondo rosso (1975) and

Tenebre (1982), and Bruno Nicolai's score for Emilio Miraglia's

La dama rossa uccide sette volte (1972).

The visual aesthetic is oftentimes as impressive as the aural. Exteriors (of which there are very few beyond the opening and closing credits) are obviously miniatures, with very little effort to make them look photorealistic. This sets an otherworldly tone right from the start, as if the film is taking place in a slightly alternate reality, as the real and the fake mix together in Reed's confused mind. Interiors are blank, as if they are show-houses, not actually inhabited by a flesh and blood person – one shot, for example, shows a drink's cabinet where the bottles have no brands, just the name of the alcohol. Again, this sets the film's reality apart, as if everything is happening just outside our own world, or our own conception of the world. There are also a couple of nods to the master of body horror, David Cronenberg – a stomach wound pulses and expands as if breathing, a gigantic beetle crawls out of a toilet and infects a character's face, scissor wounds are curiously fingered, a character's ear is split open with a tin opener. It's all very Disney!

Ultimately, however,

Piercing is more interested in aesthetics than exploring the psychology of the characters. The increasingly extreme goings-on are never anything more than a jokey end unto themselves, with the psychological path that has led the characters to these extremities relatively ignored. With Pesce focused on comedy beats, there are certainly a few laughs, but there's precious little substance. He's undoubtedly adept at evoking the most absurdly grotesque comedy, but he is, thus far in his career, equally as uninterested in developing character or plot. And for that reason, the film comes across more like a calling-card than a self-sustained and complete product.