Reasonably well made, but barely scratches the thematic surface

This is a circus. The consequences will extend long past my nomination. The consequences will be with us for decades. This grotesque and coordinated character assassination will dissuade competent and good people of all political persuasions from serving our country.

- Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh; addressing the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary in relation to several accusations of sexual assault (September 27, 2018)

We're all going to have to seriously question the system for selecting our national leaders, that reduces the press of this nation to hunters and presidential candidates to being hunted, that has reporters in bushes, false and inaccurate stories printed, photographers peeking in our windows, swarms of helicopters hovering over our roof and my very strong wife close to tears because she can't even get in her own house at night without being harassed. And then, after all that, ponderous pundits wonder in mock seriousness why some of the best people in this country choose not to run for high office.

- Gary Hart withdrawing from the 1988 Democratic Party presidential primaries after being accused of infidelity (May 8, 1987)

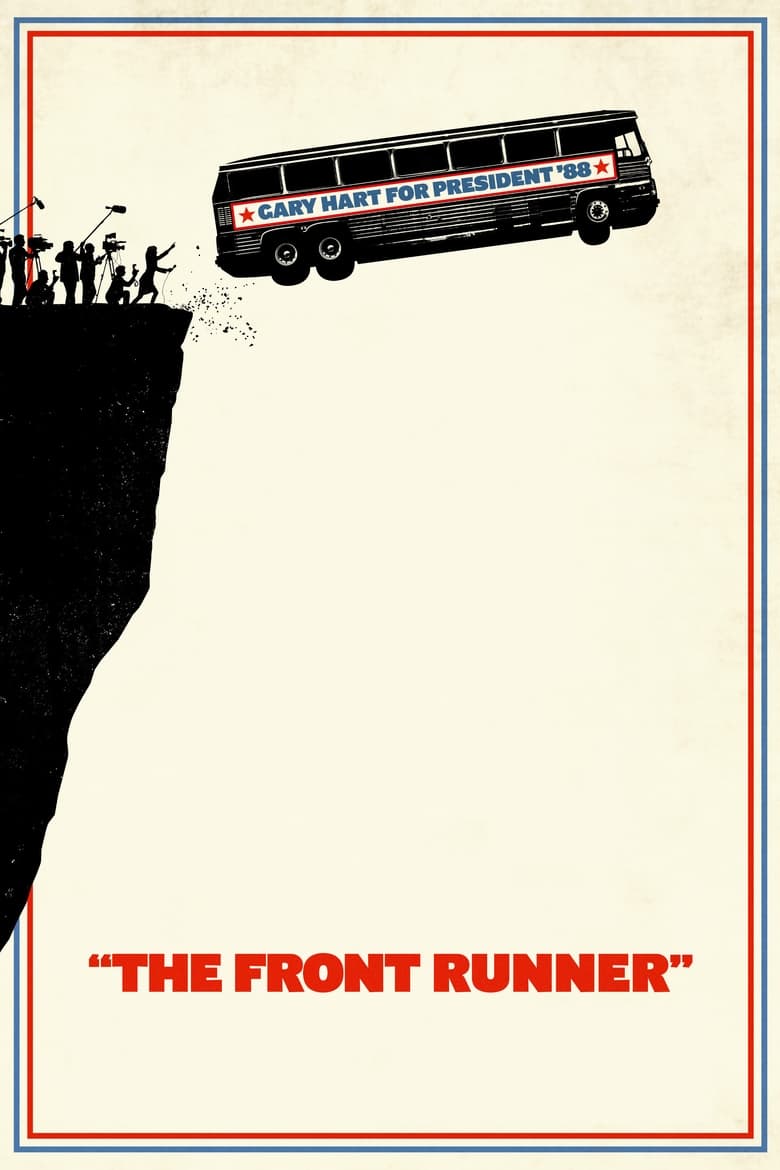

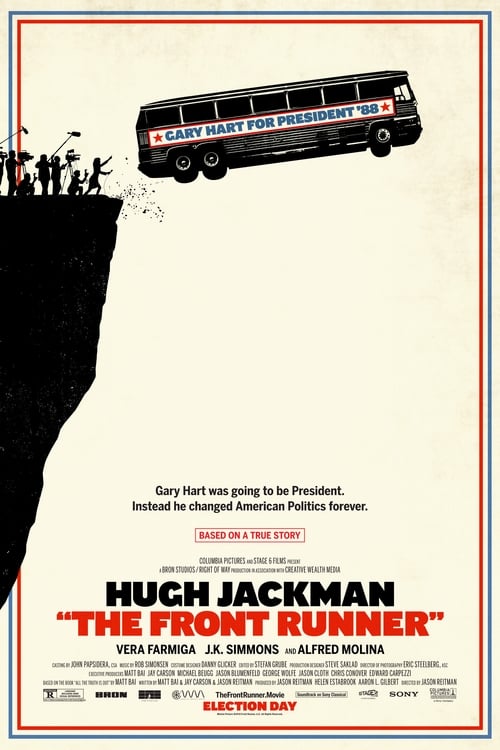

Based on the non-fiction book

All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid (2014) by Matt Bai, written for the screen by Bai, Jason Reitman (

Thank You for Smoking;

Juno;

Tully) , and Jay Carson (Hilary Clinton's former press secretary), and directed by Reitman,

The Front Runner tells the story of Colorado senator Gary Hart's doomed 1988 presidential campaign. The most likely candidate to win the Democratic nomination, Hart's reputation was shattered when a

Miami Herald story accused him of an extramarital affair, and only three weeks into his campaign, he withdrew from the race. The film presents the events of those weeks as a seismic turning-point; when political journalism and tabloid sensationalism irrevocably fused, when private scandal became just as important to the American public as political acumen, perhaps even moreso. Aspiring to the kind of multi-character canvas of Robert Altman or early Paul Thomas Anderson,

The Front Runner recalls Altman's 1988 miniseries,

Tanner '88. However, it spreads itself far too thin, trying to take on the perspective of a plethora of characters, yet telling us very little about any of them, least of all Hart himself. And in the end, it fails to work as either a darkly satirical examination of the Hart scandal, or as a socio-political critique of the current constitutional environment in the US.

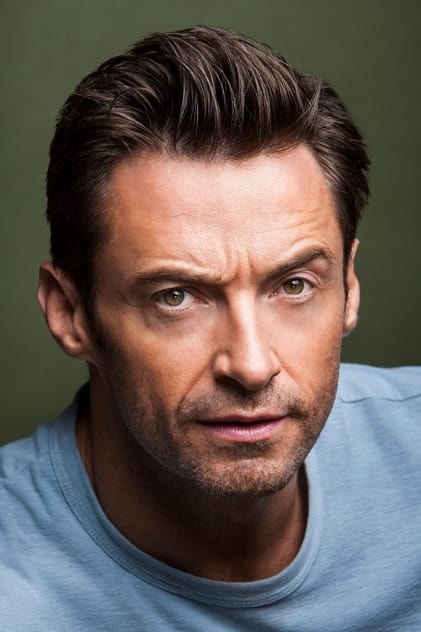

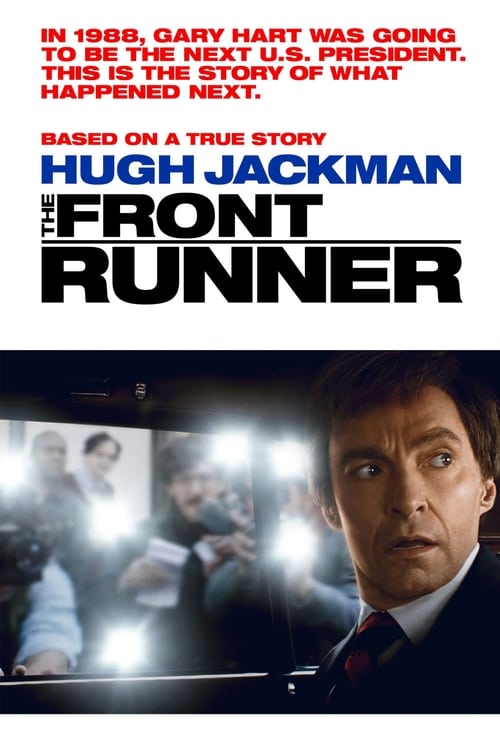

The film opens in 1984, with Hart (Hugh Jackman) conceding the Democratic primary to Walter Mondale, who stands virtually no chance of defeating incumbent president Ronald Reagan. Three years later, Hart runs again, and this time he is the clear favourite not just to secure the nomination, but to defeat Vice President George H.W. Bush, who was offering the country essentially the same policies that had been seen during Reagan's two terms. Dogged by rumours of infidelity, Hart firmly believes he is entitled to privacy, and that what he does on his own time should have no bearing on his ability to govern. Exasperated at being repeatedly asked about his private life, he challenges the media to follow him, telling them that if they do, they will be very bored. However, after receiving an anonymous tip that Hart is in the midst of an affair, Tom Fiedler (Steve Zissis) of the

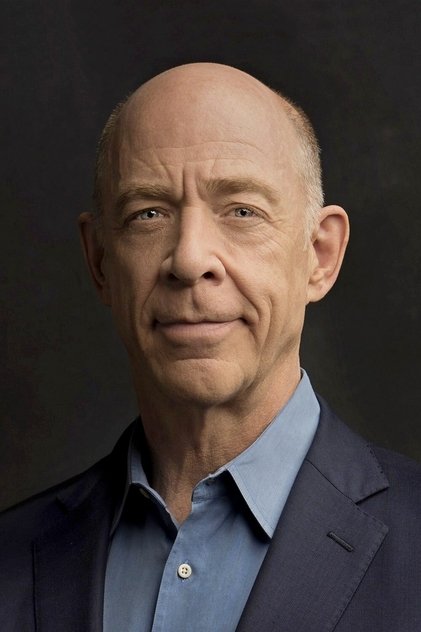

Miami Herald calls his bluff, following him to his Washington town house and seeing him enter with a woman who doesn't come back out. Over the next three weeks, Hart's campaign implodes, with the film detailing how that implosion is dealt with by a number of people, including his wife, Oletha "Lee" Hart (Vera Farmiga), who had asked only that he never embarrass her in public; his campaign manager, Bill Dixon (J.K. Simmons), who tried to warn Hart that the private and the public had become one;

Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee (Alfred Molina), who was reluctant to wade into what he saw as tabloid territory; Hart's alleged mistress, Donna Rice (Sara Paxton), who was portrayed in the media as a bimbo homewrecker; fictional

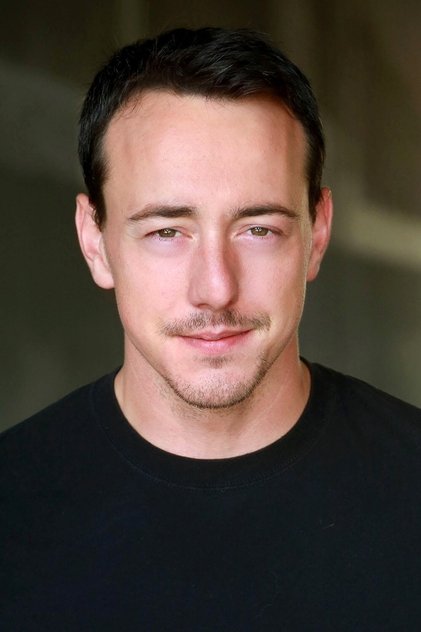

Washington Post reporter A.J. Parker (Mamoudou Athie), who covers the story with no small amount of distaste; fictional campaign scheduler Irene Kelly (Molly Ephraim), who promises Rice that she will keep her name out of the media; campaign press secretary Kevin Sweeney (Chris Coy);

Washington Post reporter Ann Devroy (Ari Graynor), who believes strength of character is just as important in a presidential candidate as policy; fictional

Miami Herald publisher Bob Martindale (Kevin Pollak), who stands by the journalistic integrity of his paper; and Hart's daughter, Andrea (Kaitlyn Dever), who came out as a lesbian just prior to the scandal.

Although the film doesn't absolve Hart of being a terrible husband, it does present him as an inherently decent man trying to protect his privacy, and that of his family, against a predatory and newly mercenary media. Depicting it as more concerned with prurience than rhetoric, the film takes a dim view of the Fourth Estate - its antecedents are films such as Billy Wilder's

Ace in the Hole (1951), Sidney Pollack's

Absence of Malice (1981), and Costa-Gavras's

Mad City (1997) rather than, say, Michael Mann's

The Insider (1999) or Tom McCarthy's

Spotlight (2015). Following the line of the book, Reitman posits that the

Miami Herald and Fiedler (who is, along with Martindale, the

de facto villain) did Hart himself, the American people, and political discourse in general a grave disservice insofar as tabloid reporting of this nature has gone on to undercut serious political debate, and has thus subverted the importance of the political process, cheapening it by way of cynicism, sensationalism, and sleaze.

Although ostensibly about the events of 1987, much like Spike Lee's

BlacKkKlansman (2018),

The Front Runner has one eye on the here and now, musing as to why a man who was merely accused of having an affair (an accusation that was never proved) had his political career destroyed, and yet a man accused of sexual misconduct on multiple occasions, a man who is on tape bragging about how he can sexually assault women with impunity, could be elected to the highest office in the land. The answer suggested by the film is that, since Hart, scandal has become just another aspect of politics, and that which destroyed Hart in 1987 barely made a dent on Bill Clinton in 1998 or Donald Trump in 2016. In this sense, lines such as Devroy's "

anyone running for president must be held to a higher standard" are as much about Trump as they are Hart.

Essentially, the film argues that the country now has a president like Trump precisely because of what happened to Hart, and in this sense, perhaps its most salient theme is that the Hart scandal represents the point at which politics became a form of entertainment, opening the floodgates to the tabloids, whilst Hart himself became a martyr to this new style of political coverage. The film drives this message home by having Bradlee tell a story about Lyndon B. Johnson, who, upon becoming president in 1963 told the media, "

you're going to see a lot of women coming and going, and I expect you to show me the same discretion you showed Jack." The media ignored the infidelities of Johnson and Kennedy (and Franklin D. Roosevelt), reporting only on their political activities, and Hart sees no reason why things should be any different for him. In this sense, his blindness is his

hamartia, ignoring Dixon when he tells him, "

it's not '72 anymore Gary. It's not even '82". The landscape had changed, and Hart's inability to change with it cost him everything.

However, despite the fact that all of that should make for fascinating drama,

The Front Runner doesn't really work. The most egregious problem is the depiction of Hart himself. For starters, it's questionable, at best, to portray him as the victim of an increasingly combative media, glossing over the fact that he himself was the architect of his ruination, sabotaging his own political career and humiliating his wife all because of his libido. In this post-#MeToo era, suggesting that a powerful man was wronged when he was exposed cheating is more than a little naïve. Indeed, the film seems to yearn for simpler times, when potentially great men could walk the path to positions of power, unimpeded by intelligent women speaking out against them, or diligent reporters uncovering their less wholesome activities, when infidelity remained hidden from the public.

The Front Runner is not a story about a man who learns that private ethical lapses have become intertwined with public policymaking. Instead, it's about a man who was unfairly destroyed by a pernicious press for doing exactly the same thing that his predecessors had gotten away with for decades. And that's a much less interesting film.

Additionally, due to a poor script which offers Jackman little in the way of an arc, Hart barely registers as a real person, with little sense of interiority or psychological verisimilitude. Instead, he comes across as a blank slate, a cypher onto which the audience can project its own interpretation. Related to this, Reitman tells us that Hart was an outstanding candidate, offering things that others did not, and had it not been for the insidious media, he would have gone on to become a sensational president. However, the film never gets into the specifics of how exactly he was so different, what he offered that was so unique, or why he would have been such a good POTUS. Reitman asks the audience to take Hart's potential for transformative greatness on trust, never attempting to illustrate any aspect of that potential, a failing which significantly undermines his condemnation of the media.

Elsewhere, the film tries to touch on virtually every aspect of the scandal – reporter-editor meetings discussing the moral responsibility of the press; campaign staff trying to fight back against tabloidization; gumshoe reporters hiding in bushes and stalking back alleys; the strain on Hart's marriage; the effects on Donna Rice. Ultimately, it casts its net far too wide, briefly covering topics that are crying out for a more thorough engagement. For example, at one point, Rice says to Kelly, "

he's a man with power and opportunity, and that takes responsibility." That's a massive statement with a lot of thematic leg-work already built in, and serious potential for probing drama, but the film fails to do anything with it, moving on to cover something else. Indeed, Sara Paxton, despite given only two scenes of note, gives a superb performance, finding in Rice a decency and intelligence, playing her as someone who wants to keep her name out of the press because she doesn't want to embarrass her family. She's an infinitely more interesting figure than Hart himself, and the film would have benefitted immeasurably from more of her.

In its November 2018 issue,

The Atlantic carried an article by James Fallows looking at the alleged death-bed confession by Republic strategist, former adviser to both Reagan and Bush, and current head of the Republican National Committee Lee Atwater that he had orchestrated an elaborate set up of Hart so as to ensure he didn't run against Bush in the election. Obviously, this story only came to light after the film had already been shot, but it isn't even mentioned in the bland one-line closing legend, which tells us only that Hart and his wife are still married today.

The Front Runner is aesthetically fairly solid; well-directed, well-shot, well-edited. However, given how thematically relevant the Hart story is to the contemporary political climate in the US, especially the increasingly antagonistic relationship between the White House and the media, the script feels bland and overly simplistic. The core of the story is the question of whether or not the press was right to report on Hart's infidelity. Did the public need to know? Did it have any bearing on his ability to lead? The film answers all three questions with a resounding "no". However, the cumulative effect is of a scandal skimmed rather than explored, of characters glanced at rather than developed, of controversies summated rather than depicted. There are some positives – Farmiga and Paxton are both excellent, for example – but all in all, this is a missed opportunity, lacking both socio-political insight and satirical flair.