Stephen Campbell

May 22, 2019

8/10

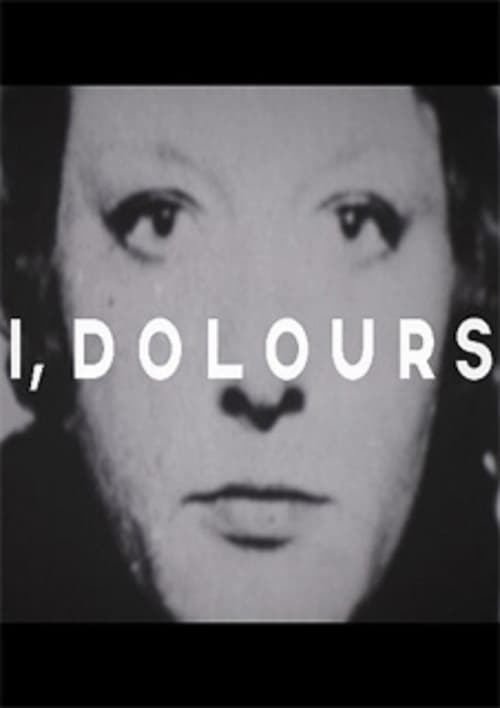

The things we have in common from our past, long past, are often in my mind. Now that it is all over bar the final destruction of the weapons I look forward to the freedom to lay bare my experiences unfettered by codes now redundant.

This is the only freedom left to me and those Republicans of like mind.

I should wish you well, Gerry, but my heart is too heavy to feel it and I cannot be a hypocrite. I have no regrets. My trust was abused.

- Dolours Price; "An Open Letter to Gerry Adams" (July 31, 2005)

she was threatening to go public with everything. That would have caused enormous damage to herself, to her family, to all sorts of people. I felt I had a duty of care for her. I went to her and said: 'Dolours, you can't do this. But if you want to ensure that your story gets out, then fine, we'll sit down and we'll do it. We'll tape-record it. And then when you are dead – presuming I am still alive – I will fulfil a promise to make sure the film gets made'.That interview forms the basis for I, Dolours. As an aside, it's worth pointing out that McIntyre was not involved with the making of the film, and refuses to condone it, telling The Irish News,

I declined to have a role in this documentary, because I don't feel we can on the one hand criticise The Irish News and then on the other hand publish our own story. It doesn't add up to me. I would really have to stretch logic to justify this. I can only say from my own perspective. I think the criticism of The Irish News from Ed's perspective certainly becomes invalid.Moloney, for his part, has written on his blog,

the interview with Dolours Price was devised and conducted in an effort to prevent her from taking her story in an indiscriminate way to the media with incalculable consequences for herself and her family. She was seemingly determined to make her story known, but in an uncontrolled way … The terms of the interview were simple and straightforward. Dolours would give her interview, the original film would be stored away in Ireland and when she died, her story could then be told. I told her that if she predeceased me then I would do my best to tell her story in a truthful and accurate way. If I died first it would be left to others to complete the task. The details of this arrangement were agreed not just between myself and Dolours Price, but were agreed by Anthony McIntyre.So what exactly is so important about Price's testimony; what does she say that has precipitated a dispute involving two newspapers, five reporters, and an American university, leading to a controversy within Irish journalism that shows little signs of abating (and that's even without mentioning the US Department of Justice's 2011 subpoena of the Boston archive on behalf of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), and the resultant legal controversy). In short, what does Price say that prompted Moloney to hold onto the interview until after her death? Well, for one, although she claims the Unknowns was run by Pat McClure, she states that he "reported back to the Officer Commanding in Belfast – who would have been Gerry Adams." She also alleges that it was Adams who selected the personnel to carry out the Old Bailey bombing. Certainly, this is not the first time he has been accused of this. The claim is also made in Moloney's Secret History, and in a 2007 Boston archive interview with Brendan Hughes, former Officer Commanding of the IRA's Belfast Brigade, although the full interview was not made public until 2013. Adams has always denied it, indeed, he denies ever being a member of the IRA at all, and Price's claims in I, Dolours are sure to reopen the debate. However, the real significance of her interview is the information she provides about four of the Disappeared; Joe Lynskey, Jean McConville, Kevin McKee, and Seamus Wright. According to Price, her task was to transport those marked for death across the border into the Republic of Ireland, where she would hand them over to Dundalk volunteers, after which they would be killed and buried. With the four murders taking place over three missions (McKee and Wright were transported together), Price claims that in two cases, she was simply the driver, but in the third, that of McConville, she was forced to adopt a more hands-on role. And it is here, specifically, where the documentary is at its most controversial, and its strongest. For the most part, Price shows no remorse for her actions, arguing, "we believed that informers were the lowest form of human life," emphasising that she disagreed with the tactic of Disappearing, believing instead the bodies should be dumped in the street "to put the fear of God" into anyone who may have been thinking of informing. The only time she exhibits any signs of real regret is when relating the murder of Joe Lynskey (one of the few people Disappeared for reasons other than informing). Describing him as "a gentle, gentle man," Price explains that as she transported him, she wished he would jump out of the car and make a run for it, rather than willingly accepting his faith. She shows no such feelings, however, in relation to McConville, whose murder remains one of the most controversial and hotly disputed incidents of the Troubles. A widowed mother of ten, McConville's case is so contentious that no one can even agree as to why she was labelled an informer in the first place. When the IRA first acknowledged the Disappeared in 1999, they stated that McConville had had a radio transmitter hidden in her flat, which she used to send information to the British Army, in return for money. However, it was argued at the time that, as a widow trying to raise ten young children, she wouldn't have had access to sensitive information, let alone the time to pass it along. Additionally, in 2006, a report by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland found no corroborating evidence suggesting McConville had been an informer. According to Price, however, the IRA knew she was informing because of an entirely different reason. She claims that McConville was working on identifying suspects from Hastings Street police station in Belfast by way of standing behind a blanket with a small slit for her to look through. However, the blanket didn't come to the ground, and one of those brought in front of her claims he recognised her slippers. Not only does Price show no regret regarding her role in McConville's death, she seems to recall it with a sense of pride, pointing out she found McConville "very arrogant", and that during their trip south, McConville, who didn't know the fate awaiting her, said: "I knew those Provo bastards wouldn't have the balls to shoot me." Numerous people, however, have refuted this, saying McConville would never have spoken in such a manner. Another problem with Price's version of events concerns the revelation regarding her own involvement in the actual murder. As Price tells it, "the Dundalk crew didn't want to do it. They couldn't bring themselves to execute her. Probably because she was a woman." As a result, Price, McClure, and an unidentified third person took McConville to a shallow grave and shot her in the back of the head. She doesn't say which one fired the initial shot, but she does state that the trio deliberately assumed a shared responsibility; their single pistol was passed around, and "the other two volunteers each fired a shot so that no one would say that they for certain had been the person to kill her." The problem with this is that it is not borne out by the evidence. McConville's remains were discovered in 2003 on a beach on Cooley Peninsula, yet an autopsy found only one bullet wound, and no other bullets in the area. If events played out as Price claims, two of the three shooters missed, and the bullets have never been recovered. Interestingly, however, as the above quote illustrates, as Price describes the murder, she slips into the third-person, recounting the incident as though it was someone else involved, even though it is clear she is speaking of herself. Whilst the film is definitely at its best when dealing with the McConville murder, its handling of other aspects of Price's story are also laudable. For example, it does a fine job of tracing her ideological development, particularly as it relates to her family. Speaking of her father's role in S-Plan, Price proudly describes how he went to the UK "to fight the imperial master", and also recalls how he later told her, "I blew them up before you did. The only difference is I didn't get caught". Additionally, the film spends time dealing with Price's aunt, Bridie, an IRA volunteer who lost her hands and eyes in an accident handling grenades when she was 25. Although Price hated the job, she would sit with Bridie, holding her cigarette, obviously proud of the older woman's commitment, and feeling compelled "to validate her sacrifice." In this sense, the film is very much about the seductive power of some of the more romantic myths of Irish Republicanism (they're not terrorists killing innocent people, they're volunteers fighting colonial oppressors, sacrificing everything for the good of the Irish nation) contrasted with the savage day-to-day reality of waging a guerrilla war (there is some horrific footage of bomb victims). The film makes it extremely easy to see the attraction of the sectarian moral code under which Price operated, and into which she was indoctrinated as a child; the absolute and unrelenting desire to unite Ireland by any means necessary, the goal of such historical titans as Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-1798), Bartholomew Teeling (1774-1798), Robert Emmet (1778-1803), William Tennant (1759-1832), James Stephens (1825-1901), Tom Clarke (1858-1916), and Pádraig Pearse (1879-1916). It's good company for a directionless young Catholic in a majority Protestant state, and the attractiveness of such ideological rigidity is cogently presented. The film clearly and concisely charts Price's radicalisation as she transitions from civil rights activist to convicted bomber to hunger striker to peace process critic, detailing, for example, her participation in the 1969 People's Democracy march that ended at Burntollet Bridge with Loyalists attacking the peaceful protestors, as the Royal Ulster Constabulary refused to intervene. Like many of her generation, Price sees this as a decisive turning point in Ulster Republicanism, realising of the Loyalists and Unionists, "I'm never going to convince these people." Interspersed with the interview material and archive footage, there are a number of reconstructions, with Price played by Lorna Larkin. According to director Maurice Sweeny,

there was an element of necessity there because first there wasn't a huge amount of archive of Dolours herself, or her family. She'd been in prison for eight years of the key times we're talking about. We had that one voice, we didn't have other interviews, because we'd made that editorial decision. I suppose the word 're-enactment' is often used, but I kind of see it as more of a visual memory of hers in the film. We have three: we have an archive of the North, bombs, riots, which is quite frenetic visually on screen. Then we had a standalone sit-down interview. And I just wanted something to go from her narrative, in and out of her childhood, her time in prison. It's always very hard to get those right. We were very careful about how we shot it. We cut the film, almost, before we shot it, because we had that bed of an interview. It was almost her looking back at those iconic moments in her life.Aesthetically, these reconstructions are quite interesting, insofar as they often feature Larkin, in character, speaking directly to camera – an unusual stylistic device in a documentary already featuring a lot of interview footage, but one which works because it fortifies the central organisational principal; this is her account of events. By employing such a subjective approach in the film's only ostensibly objective sections, this impression is enhanced even further. Towards the end of I, Dolours, Price refers to the Good Friday agreement as "a failure of my life's purpose," arguing "I wouldn't have missed a good breakfast for what Sinn Féin achieved," and subsequently, one of the last things she says is, "It's all been for nothing." This can come across as either the deeply tragic end to a life lived for her country, or the just deserts for a murderer, depending on your politics. And the fact that her story is so emotive, irrespective of which side of the debate upon which you fall, speaks very much to the quality of the work in which that story is presented. Powerful, contentious documentary filmmaking of the highest calibre, I, Dolours should be made required viewing in Irish schools, north and south of the border.