A gift for the fans, especially those of us who have long extolled just how pioneering the show was

At zero-eight-hundred hours, station time, the Romulan Empire formally declared war against the Dominion. They've already struck fifteen bases along the Cardassian border. So, this is a huge victory for the good guys! This may even be the turning point of the entire war! There's even a "Welcome to the Fight" party tonight in the wardroom...So...I lied. I cheated. I bribed men to cover up the crimes of other men. I am an accessory to murder. But most damning of all...I think I can live with it...And if I had to do it all over again...I would. Garak was right about one thing - a guilty conscience is a small price to pay for the safety of the Alpha Quadrant. So I will learn to live with it...Because I can live with it...I can live with it...Computer - erase that entire personal log.

- Cpt. Benjamin Sisko; Final words of "In the Pale Moonlight" (first aired, April 15, 1998)

Premiering in syndication on January 3, 1993 and ending with the broadcast of its 176th episode on June 2, 1999, the thing that I loved most about

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine was the very thing that made Trekkies hate it - it just didn't feel like

Star Trek. At least, not entirely. The Gene Roddenberry-created

Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-1969) and

Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994) were both shows built around idealism, depicting how by the time of the 23rd and 24th centuries, humanity had put aside its petty squabbles, created global political harmony, and even done away with money, with Earth itself now a veritable utopia. Meanwhile, the human-led United Federation of Planets were very much the good guys, with Starfleet as the always-honourable, morally irreproachable

de facto police force of the galaxy, facing off against the nefarious Klingons, Romulans, Gorn, Tholians, Ferengi, Borg etc. They were shows about exploration and diplomacy, but above all, they were shows about optimism, about how humanity can rise above any adversity, about how hope should never be lost.

And then came

Deep Space Nine, or, to use a moniker originally intended as derogatory, but which has since been appropriated as a badge of honour by the show's makers and fans, "dark

Star Trek". And what was so dark about it? Well, by way of illustration, let's look at the sixth season episode "In the Pale Moonlight", regarded by some (myself included) as the finest hour of the entire

Star Trek franchise, and by others as the episode where

DS9 most egregiously violated the edicts of Roddenberry's creation. Deep into the Dominion War, (the concept of a prolonged and costly war, in and of itself, was fairly antithetical to the idealism of the franchise), the Federation and the Klingon Empire had been getting their asses handed to them for months by the Dominion (again, in Roddenberry's original conception, the good guys rarely lost). With the Romulans reluctant to get involved in a conflict that has little to do with them, they are tending towards a wait-and-see approach. However, Starfleet knows that if the war continues along the same lines for much longer, there will be no way back. And so, in an effort to ensure the Romulans enter the war, Captain Benjamin Sisko (the legendary Avery Brooks) lies, cheats, cajoles, and is a party to murder. And if that isn't bad enough, not only does he admit in his personal log that he would do it all again if he had to, he then erases the log entirely. This was psychological territory totally alien to Trekkies, raising the kind of moral questions one simply never encountered when dealing with such idealised characters as James T. Kirk (William Shatner) and Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart). This was some seriously dark material. This was not

Star Trek.

And, on that point, I agree. This was not

Star Trek. This was better.

Although created by Rick Berman and Michael Piller, the real creative force behind

DS9 was executive producer and lead writer Ira Steven Behr. With Berman and Piller focusing their attention on

Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001), from

DS9's third season onwards, Behr was essentially left to his own devices (and if

DS9 is "dark

Star Trek",

VOY is "

Star Trek for kids"). And, much like Michael Mann's involvement with

Miami Vice, you can almost pinpoint the exact moment when Behr took hold of the reins (although in the case of

Miami Vice, it was a dramatic dip in quality upon Mann's departure). From the last episode of the second season ("The Jem'Hadar"), Behr and his exceptional team of writers (Robert Hewitt Wolfe, Ronald D. Moore, Hans Beimler, and René Echevarria) would set about crafting a pioneering show that did things and went places not only unique for the

Star Trek franchise, but unique for syndication entirely. Long before the Second Golden Age of Television,

DS9 occupied a fascinating middle-ground between the episodic storytelling of

TNG and the serialisation format employed by most shows today. Indeed, it has more in common with today's binge-worthy long-form narratives than with any of its contemporaries. This is one of the reasons why it has proved so popular on Netflix in recent years - it lends itself to watching six or seven episodes at a time so as to get a better sense of the overarching narrative tapestry, a tapestry which

TOS,

TNG, and

VOY simply didn't have. Often criticised at the time (if you missed even one episode, especially in the heavily serialised last two seasons, you could easily get lost), this style of storytelling is exactly what's expected by people who've never known life without streaming, and partly because of this, the show has aged extremely well.

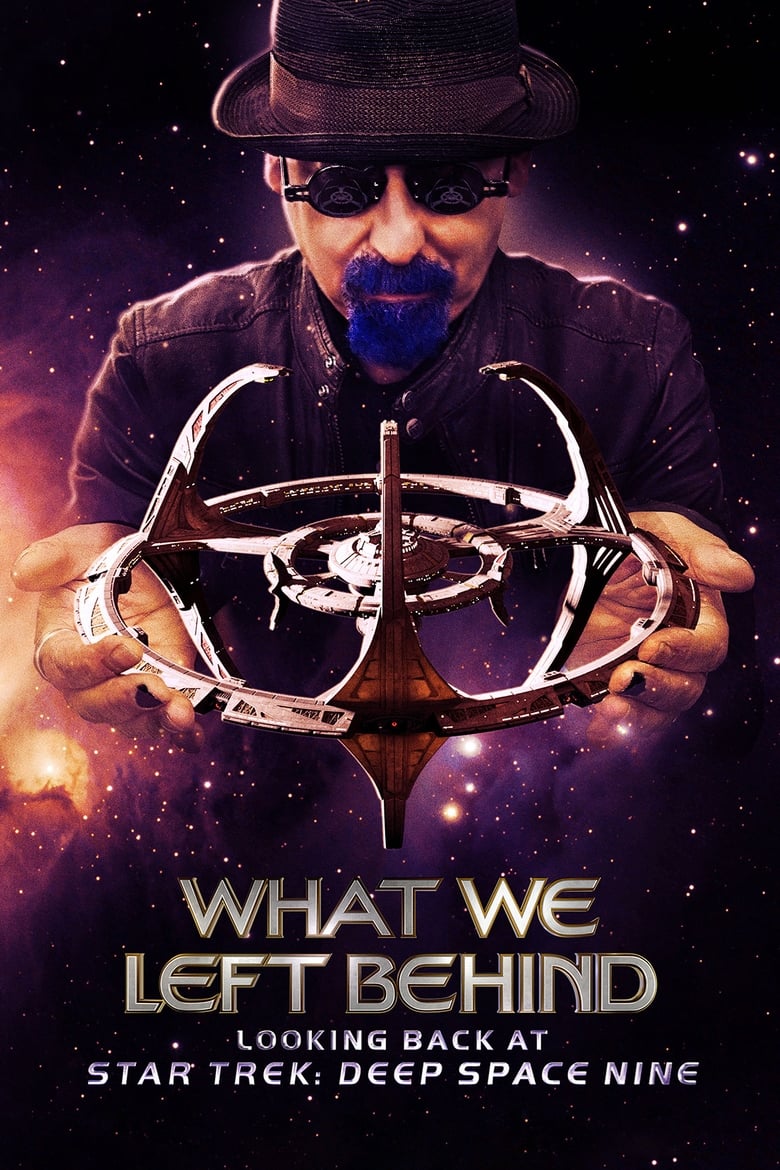

All of which brings us to

What We Left Behind: Looking Back at Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, a partly fan-funded documentary directed by Behr and David Zappone. The documentary is built around three core components; the cast and crew looking back at their time on the show (often very emotionally), a writers' room mapping out the first episode of a hypothetical eighth season (which ends up sounding awesome), and everyone from military vets to clergy to TV producers to human rights campaigners to professors of history discussing just how ahead of its time the show really was. And thankfully, the documentary is absolutely superb, and something no

DS9 fan can possibly miss.

In 2017, Behr announced that he had reassembled most of the cast and many of the crew for an as-yet unnamed documentary. Partly complete, he explained that they were lacking sufficient funds to scan the original camera negatives and convert them to HD. With the documentary featuring 22 minutes of original clips, Behr explained they were only planning to convert a couple of minutes, with the rest being left in their original broadcast 480i format. Setting up an Indiegogo fundraising page to crowdsource the rest of the capital, the fund surpassed its target of $150,000 less than 24 hours after going live. Going on to raise over $631,000, the documentary team ultimately decided to convert all 22 minutes of original footage.

Which brings us to an important point that I simply can't over-emphasise; it's worth the price of admission just for these 22 minutes.

TOS and

TNG have already had their 1080p conversions, but

DS9 has only ever been seen in 480i, even on Netflix. With that in mind, the documentary offers a unique opportunity, possibly the only opportunity fans will ever get to see parts of the show in full HD (in 2017, Treknews.net published a fascinating interview with Robert Meyer Burnett, who was in charge of the

TOS and

TNG Blu-rays, where he explains in great detail why it's unlikely

DS9 or

VOY will ever be converted to HD for any medium). Obviously, the space stuff looks truly amazing, with the epic battle scenes from "Sacrifice of Angels" standing up against anything you'd see in a big-budget movie in terms of scope and elaborateness. However, even the smaller character moments really pop - the colours are so much richer (especially the reds and blues in the uniforms), the blacks and shadows so much deeper, the makeup more nuanced, the subtlety of background detail more noticeable.

In a roundtable with Behr, Zappone, and producer/editors Joseph Kornbrodt and Luke Snailham, shown after the screening I attended, even Jonathan West, the show's director of photographer from the third season on, is shown as being amazed at how good the original footage looks after the conversion process. And not only is it in HD, it's also in 16:9. Like

TNG,

DS9 was originally shot on 35mm before being converted to video for editing, and broadcast at 1.33:1. However, unlike

TNG,

DS9 was framed to protect for widescreen (meaning that although it was shot with the intention of being converted to 1.33:1, so too was it composed as if widescreen was the intended goal). The same is true of

The Wire, which was broadcast at 1.33:1, but converted to 1.78:1 for its Blu-ray release, a process made easier by the fact that it was shot to protect for widescreen. And as anyone who has seen

The Wire's magnificent 1080p/1.78:1 conversion will attest, the difference is night and day. In the roundtable, there are some split-screen comparisons between the clips as they originally aired and as they appear in the documentary, and it's like watching a completely different show. It's definitely my inner nerd coming out, but some of the footage gave me goosebumps. Literally.

The film begins with the cast reading extracts from some of the criticisms aimed at the show in its early years - mainly revolving around the fact that it wasn't

TOS or

TNG, that it was too dark and morally ambiguous, that it wasn't as good as

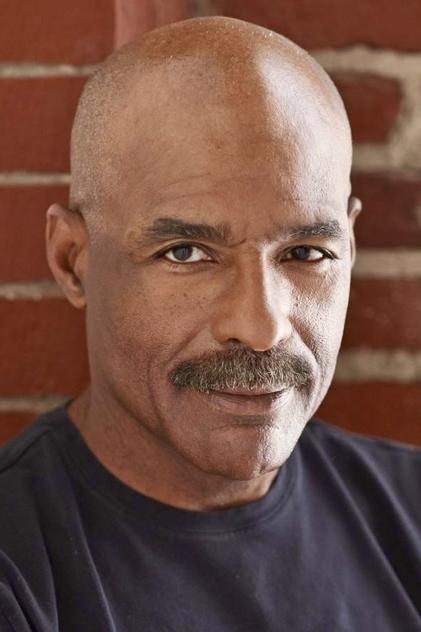

Babylon 5 (the temerity!), that it was on a station instead of a ship (how could it "boldly go" when it couldn't go anywhere, boldly or otherwise), that there were too many non-Starfleet characters, that the characters were too flawed. And whilst these criticisms are played for laughs, Behr and Zappone don't shy away from looking at some of the more painful moments - Avery Brooks being forbidden from having a goatee and a shaved head, so as not to appear, to quote then Paramount Television chairman Kerry McCluggage, "

too street" (as Behr points out, "

we were expecting Avery Brooks, one of the coolest cats on the planet, and instead we got the boring dad version of Avery Brooks"); Rick Berman not understanding why Behr wanted to introduce a war storyline, and later complaining that the show had become too violent (leading to Ronald D. Moore's famous rejoinder, "

it's a fucking war! What do you mean it's too violent?"); Terry Farrell (who played Jadzia Dax) asking to be written out of the show with only one season left because she felt she was being mistreated behind the scenes; the entire cast (except Colm Meaney) not being especially happy with the arrival of

TNG's Michael Dorn in the fourth season; the lesbian kiss in the fourth season episode "Rejoined" that ignited huge controversy; the psychological toll that playing Benny Russell in the sixth season masterpiece that is "Far Beyond the Stars" took on Avery Brooks (who also directed the episode, brilliantly, I might add).

The film also spends a lot of time looking at some of the series' more politically-charged moments.

Star Trek in general has always done political themes very well, but whereas

TOS and

TNG tended to operate via allegory and metaphor,

DS9 was more direct, shining an unflinching light on all kinds of issues. Terrorism, for example, was built into the show's DNA in the character of Major Kira Nerys (Nana Visitor), a former member of the Bajoran Resistance who had waged a guerrilla war against the Cardassian forces during the Occupation of Bajor. This conflict was actually introduced in the fifth season

TNG episode "Ensign Ro", and the character in

DS9 was originally intended to be the titular Ro Laren (Michelle Forbes). Ultimately, however,

DS9 went much further than

TNG, depicting Kira as suffering from PTSD and crippling survivor guilt. It's especially interesting to hear Behr and Visitor talk about how the character of Kira (a freedom fighter to the Bajorans, a terrorist to the Cardassians) almost certainly wouldn't work in a post-9/11 world. The film also reminds us how PTSD was also addressed when the character of Nog (Aron Eisenberg) lost a leg in battle during the seventh season episode "The Siege of AR-558", with the next couple of episodes looking at the psychological implications of his injury. The film presents several military vets attesting how much it spoke to them to see

DS9 handling such weighty themes with dignity and grace.

Another important theme was racism, which was addressed many times, but never more explicitly or more successfully than in "Far Beyond the Stars", which is set in 1953, and depicts a writer, Benny Russell (played by Brooks), whose science fiction short stories are pulled from publication when word gets out that he's black, leading to what is hands down the most emotionally devastating and powerfully acted moment in the franchise's history. In relation to LGBTQ+ issues, the film points to the aforementioned kiss in "Rejoined" and also the long-rumoured but never confirmed theory that recurring character Elim Garak (Andrew Robinson) was in fact gay. Indeed, in relation to inclusivity, Behr laments that the show could have done better, arguing that one kiss and one rumour over seven years wasn't enough and that he should have done more, especially in terms of having the courage to reveal Garak's sexuality. It's a remarkable admission and the kind of raw honesty that's rare for a documentary made by the very people whom it is about.

Elsewhere, the film addresses how

DS9 was the only show on TV which depicted science and religion as co-existing. With most shows treating them as binary opposites,

DS9 was unique in being a science fiction show where several of the main characters were deeply religious; indeed, Sisko is even a religious icon to the Bajorans, something with which he is initially uncomfortable, but which he later embraces, with religion becoming more and more important in the show's mythology. An issue that illustrates just how little acknowledgement the show has gotten is the importance of black characters.

DS9 was not the first TV show with a black lead, that was the

Spencer for Hire spin-off

A Man Called Hawk (which starred none other than Avery Brooks), but it

was the first show to regularly feature scenes with

only black characters. When discussing this aspect of the show, Behr is unable to contain his frustration when he relates how an episode of

That's So 90s pointed to

Homicide: Life on the Streets (1993-1999) as being the first show to feature scenes of all black characters, never even mentioning

DS9. This kind of thing is something the show's cast and crew (and fans) have gotten used to over the years, but it's still somewhat upsetting to see just under the radar the show was despite the pioneering work it was doing.

And with that said, if the film has an overriding theme, it's vindication; the sense that the choices the showrunners made at the time, choices which were criticised and often not understood, have stood the test of time, with the show rightfully thought of today as unusually mature and progressive. Behr mentions, for example, how the writers always treated plot as secondary to character, something which was opposed from on-high, but they never wavered, writing stories whose primary function was to facilitate character development (contrast that with something like

Sons of Anarchy, an entertaining show, but one which buried its characters under a never-ending avalanche of plot). Another example of this vindication concerns the three-part second season opener; "The Homecoming", "The Circle", and "The Siege". The first three-episode arc in

Star Trek history, the idea was met with considerable resistance, with Paramount execs arguing that a three-parter would never work. However, as the show would go on to prove time and again (ultimately doing an unprecedented ten-episode arc in the last season), being on a space station rather than a ship lent itself to multi-episode storylines.

And one final point. The reveal of the "greatest moment in the history of

DS9", which comes during the closing credits, is one of the most epic examples of Rickrolling you'll ever see (albeit with a

DS9 twist).

Are there some problems with the film? Yes, a couple. Most notably, Avery Brooks does not appear (there is some interview footage, but it's archival). This leaves a massive lacuna in the film, not just in a practical sense, but in an emotional one as well; he was the heart of the show (and the only actor to appear in all 176 episodes), so for him not to feature is massively disappointing. However, in the years after the show went off the air, Brooks has gradually retired from film and TV acting (his last credit was

15 Minutes in 2001) whilst also appearing at fewer and fewer

Star Trek events. A tenured Professor of Theatre at Rutgers University, he hasn't done anything

DS9 related since his truly batshit insane appearance in William Shatner's

The Captains in 2011, and obviously, Behr was unable to persuade him to appear. Another problem is that with Behr conducting the interviews, there's a sense in which he lets both Berman and McCluggage off too easily, especially in relation to the Terry Farrell situation, whereas a stronger interviewer wouldn't have accepted their deflecting and ambiguous responses. Another small problem is that Behr occasionally "stops" the film entirely to intercut scripted moments, usually involving himself. As the director and primary subject, this technique crosses the line into self-indulgence, and yes, the scenes are supposed to be humorous, but they're nowhere near as funny as the off-the-cuff moments elsewhere, and they are both structurally awkward and thematically unnecessary.

That aside, however,

What We Left Behind is an exceptional documentary.

DS9's reputation as the "dark

Star Trek" is not unearned, but as the film reminds us, it was often bleak but never cynical, often pessimistic but never nihilistic. On the contrary, what the film does especially well is remind us just how humanistic the show really was, perhaps the most humanistic iteration of the entire franchise, and that any bleakness or darkness was earned by the contrasting moments of levity and humanity, by the depth of the characters and their relationships with one another. Looking at its myriad of strong women, its commentary on the psychological cost of war, its engagement with racial tensions, its marrying of science and religion, the film is about what the makers of the show left behind, but so too is it about how the show changed the future of television. The interviews with the cast and crew really drive home just how much it changed their lives, whilst the clips of fans talking about why they love it so much illustrate the extent to which it touched people. And given that

Deep Space Nine was so long maligned, considered the "middle child" of the

Star Trek family, it's ironic that, in essence,

What We Left Behind is about the love which the show has engendered.