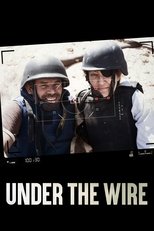

Stephen Campbell

May 26, 2019

8/10

A terrific story powerfully told

I wanted to tell Marie and Rémi's story. And those beautiful people who were being slaughtered, I wanted to tell their story. To this very day I carry the weight and responsibility of what I promised. And I'm still doing it; it's never going to stop.

- Paul Conroy

there's nowhere to run. The Syrian Army is holding the perimeter, and there's just far more ordinance being poured into the city, with no way of predicting where it's going to land.The following morning, the media centre in which the reporters were based was shelled, with both Colvin and Ochlik killed, and Conroy and Bouvier seriously injured. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the film is that the above summary only takes us to just after the half-way point. At this stage, I was thinking, "okay, so I guess the rest is going to be obituary-type material". However, that's not where it goes at all. With Colvin dead, the narrative shifts focus to Conroy, and the film basically turns into an escape thriller, as the wounded photographer seems to have little hope of making it out of the country alive (nor does the even more severely wounded Bouvier). Obviously both did, as they both give interviews in the film, but even though we know this, the fact that it doesn't dilute the heart-in-the-mouth experience of the second half of the narrative is a testament to Christopher Martin's craft and storytelling ability. For example, the film opens with a purposely disorientating shot that appears to be inside a tunnel of some kind. We later learn that it is the 3km storm drain which Colvin and Conroy used to get into Syria. However, what's especially well-thought-out about this opening is that that storm-drain proves vitally important towards the end too. This is basic narrative foreshadowing, but it's relatively unusual to see it in a documentary. Similarly, the fact that everyone in the audience knows before the film even begins that Colvin dies adds an air of foreboding that, strangely enough, reminded me of Sean Penn's use of a similar(ish) technique in The Pledge (2001). Also vital to this thriller structuring is the time the documentary takes to explain the Syrian Arab Red Crescent incident. No spoilers, but this sequence is one of the best parts of the film, providing perhaps the biggest twist in the story, and highlighting how one can find heroes (and villains) in the most unexpected of places. Under the Wire is not especially interested in contextualising the events it depicts (I've given more background on the conflict in the above couple of paragraphs than the film does), but that's because this isn't what the story is about; this is not an examination of the politics or morality of the Syrian Civil War. For example, although it explains that Homs was held by rebels, it never specifies who the rebels are or why they are fighting the government. Similarly, it never covers the theory, held by both the Sunday Times and the French government, that Colvin and Ochlik's deaths were in fact executions – that the media centre was shelled on purpose to silence the reporters stationed there; nor does it examine the fact that after their deaths, the Syrian government tried to claim the explosion which killed them was actually a rebel bomb. At the same time, this isn't a standard bio-doc – we don't get all the beats from Colvin's life, why she became a journalist, famous stories she'd written etc (there are brief references to the East Timorese and Sri Lankan incidents, but nothing else). In that sense, this is a very different animal than something like Brian Oakes's Jim: The James Foley Story (2016), which focuses very much on Foley's bio. Having said that, however, the documentary does make sure to drive home how driven, and oftentimes difficult, Colvin could be (Conroy refers to her as "a one off" and Ryan says she was "the most important war correspondent of her generation"). This is accomplished primarily by way of two stories – one in which a photographer assigned to her told his editor that she was scarier than the war they were covering, and another in which she refused to work with a photographer who identified as a metrosexual. She was a brilliant woman. No one said she was an easy woman. Apart from the thriller structure and the streamlined, non-contextualised narrative, another aspect of the story which gets a lot of attention, and which is also very well done, is the issue of reporters losing their objectivity in situations like the one in Baba Amr. Early on, Conroy relates how, as journalists, they should never allow themselves to become partisan. However, as the narrative goes on, this objectivity goes out the window, and for good reason. How does one remain objective when reporting on Dr. Mohammad Mohammad, a surgeon operating without sterile equipment or anaesthetic because had he left the basement in which he was working so as to obtain supplies, he would have been shot by snipers? How does one remain objective when reporting the story of a child injured in the shelling, dying on a table because there is no equipment to perform the operation needed to save his life? Or when reporting that he was so badly disfigured that the elderly woman acting as a nurse didn't even recognise him as her own grandchild at first and subsequently had to stand by and watch him die in front of her. According to Conroy,

I felt rage and I knew that, for Marie, this was her story and she was going to go for it whatever the cost. She decided to do as many broadcasts as possible as a plea to the world.In her final broadcast, Cooper asked Colvin why she was staying and how was she able to cover such incidents, to which she answered,

I feel very strongly that they should be shown. That's the reality. That little baby probably will move more people to think 'Why is no-one stopping this murder that is happening every day?' Every civilian house on this street has been hit. There are no military targets here; the Syrian army is simply shelling a city of cold, starving civilians.Speaking retrospectively, Conroy relates, "it wasn't war, it was slaughter." This is not journalistic objectivity. Nor should it be. Conroy knows that, in an ideal world, they should remain always non-partisan, but he is equally as aware that this is impossible in the face of the indiscriminate slaughter of defenceless civilians, and neither he nor the documentary make any apologies for that. Obviously, as the author of the book on which the film is based, Conroy anchors proceedings. Indeed, there are only a few additional interviewees (Bouvier, Ryan, Daniels, their Syrian translator Wa'el, and Colvin's colleague and friend Lindsey Hilsum). Passionate, funny, and full of nervous ticks, Conroy's talking-head material contrasts well with the terrifying footage he himself shot in Syria, and raises significant questions regarding why Assad has been allowed to remain in power, whilst also forcing the audience to consider our own attitude to the Syrian refugee crisis (try watching an elderly man and woman hobble away from the ruins of the home they have lived in all their lives, their few remaining possessions strapped to their backs, and remain detached as to the plight of these people). Conroy is also deeply emotional regarding his experiences, and one of the most moving parts of the documentary is when he views footage of a mass protest in Homs on the evening of February 22, with the people carrying banners and flags emblazoned with pictures of Colvin and Ochlik, alongside the words "We will not forget you". Conroy was unaware this had happened at the time, and had never seen footage of it before filming his interview. It's simply impossible not to be deeply moved by his reaction to the footage. And that, in a nutshell, is why this is such a strong piece of work. Equal parts emotive, stimulating, anger-inducing, and thrilling, it's a story of bravery and professional dedication in the face of unimaginable horrors, of determined humanitarianism, and absolutely impossible-to-deter dedication to giving a voice to those who so often remain voiceless.